The Opera House Fire of 1892

Early Firefighting

From the earliest days of settlement in Marathon County, fire was a threat. The mills and nearby lumberyards could easily become dangerous and destructive blazes. When such a fire started, the local population would come together and do their best to put it out.

One notable fire in 1869 broke out at the Felling harness shop on the north side of Washington Street and quickly spread to engulf Jacob Kolter’s home and music hall (then considered “the finest music hall in Wausau”). The local citizenry did their best to halt the progress of the fire by tearing down a few buildings and covering the roofs of others with wet blankets. But after the fire burned itself out, it was clear that although the community did not lack for enthusiasm in facing fires, they lacked the proper tools and organization to effectively stop them.

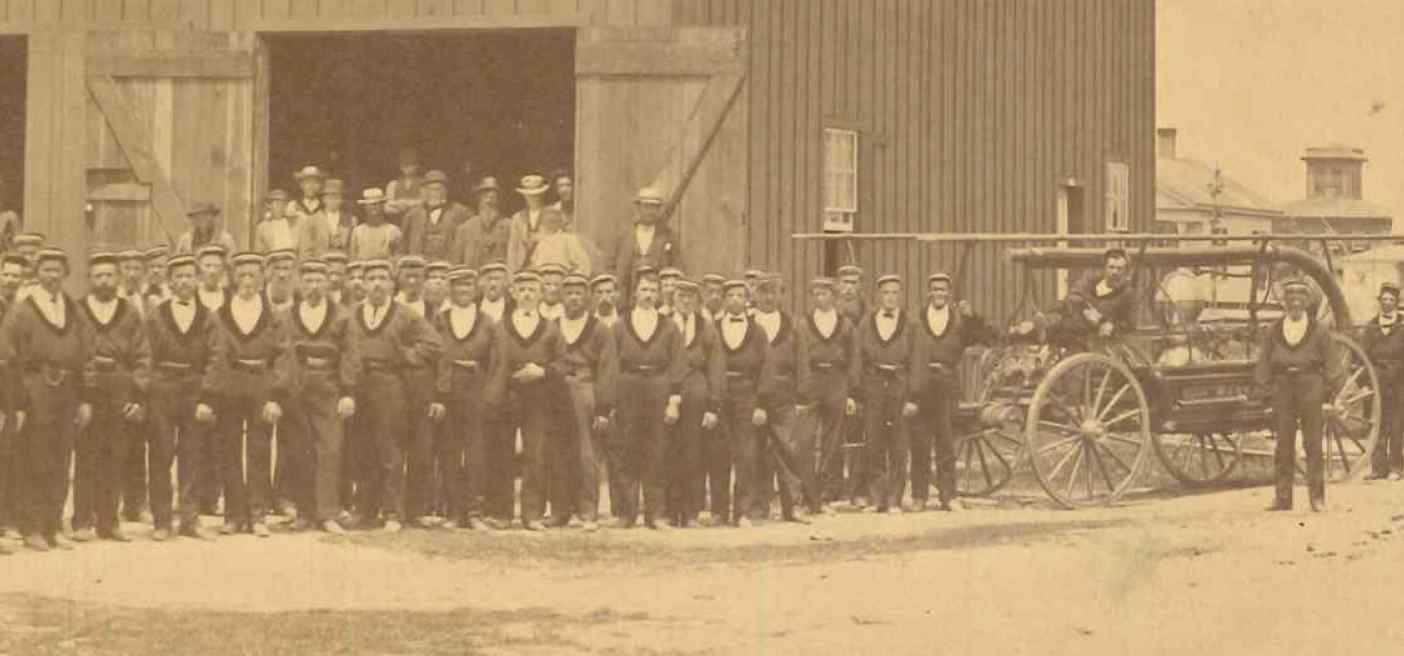

^Wausau's Volunteer Fire Company No. 1, circa 1870s

There had technically been volunteer fire fighters as early as 1862, but the 1869 fire made the need for more organization was clear to the citizens of Wausau. By the end of the year the “Volunteer Fire Company No. 1” was formally organized, a state-of-the-art fire engine was purchased by Walter McIndoe, and funds were set aside for creating a system of cisterns throughout the city. And over the next decade, the fire department did their best to protect the public from destructive blazes.

The Wood Opera House

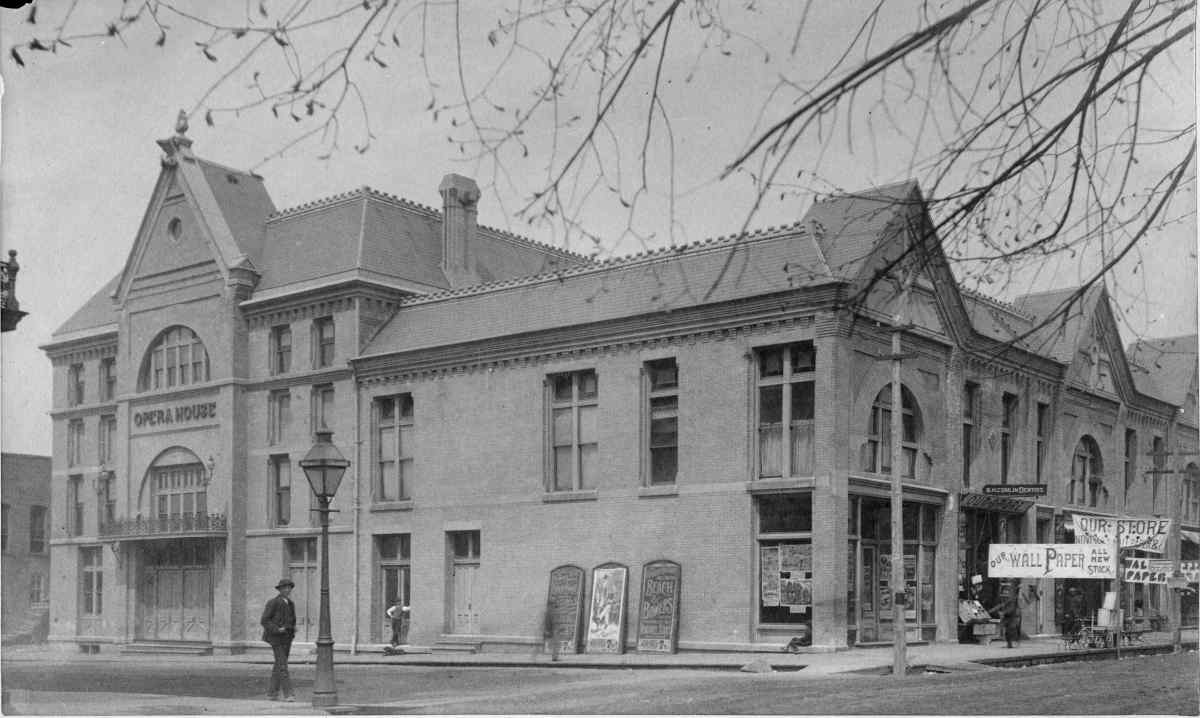

^The Wood Opera House, built 1883 on the corner of Scott and Third Streets

The Opera House on Third and Scott Streets was a building that reflected the ambition of Wausau in the 1880s. The Central Wisconsin reported of its construction in October 1883 that “they have spared neither pains nor money to make the house equal in elegance, coziness, and convenience, to any structure of the modern age, and it can be also be said that Wausau people point to their Opera House with a great deal of pride, as there is not its equal in any city of its size in the county.” Several other sources noted that it was the grandest opera house in the State of Wisconsin (with the sometimes exception of Milwaukee).

The Opera House, sometimes known as the Wood Opera House after its architect James M. Wood of Missouri, was built with fire safety in mind. The foundation included several levels each multiple feet deep, its walls were lined with 20-inch thick brick, and the trim used throughout was limestone. The ornate wooden backdrops on stage could burn and the seats might catch fire, but the building itself was surely not in much danger of being lost to a fire.

The Fire

In the early morning of January 19th, 1892, a fire was reported at the Opera House block.

A fire alarm system constructed six year earlier brought the blaze to the attention of the fire company, but a malfunction coupled with confusion over recent changes, led the teams two blocks south of the Opera House.

It eventually became clear there was no fire on Washington Street. So the fire company relocated to the scene of the real fire and the pumping teams set to work tapping the cisterns to set the hoses to use. But after a short time, the poorly maintained cistern went dry.

In this case, the cisterns containing reservoirs of water throughout the city for the fire company to access with their pumps were found to be poorly maintained. The cisterns had been an unpopular expense among the city council; only after five years of feet-dragging were the promised cisterns built, and their maintenance was poorly funded.

Admittedly, it could have been worse. In July of 1885 for example, the fire chief was criticized by in the newspapers as “[lacking] the correct information as to the location of cisterns.”

“At a recent fire, the pumping company forced water 400 feet further than was necessary. At another fire not long ago they were able to find a cistern after considerable loss of time. When they did locate one, they found that the hose was about two blocks short. A cistern within reach and able to afford the proper amount of water for protection went unnoticed.” –July 16, 1885

It might have been comical, if people’s livelihoods were not at stake. But at least in 1892, it was not the fire company’s fault.

With the cisterns dry, a team was sent with an engine to the river to pump water from there. The remaining firemen were left with little to do but wait in the cold. Many of them apparently warmed themselves with liquor from a nearby salon they had “saved” from the fire, and before the pumps were working again, many had become drunk.

In the days after the fire, The Torch of Liberty—a bastion of the few Prohibitionists in the County—jumped at the chance to blame the catastrophe on the ills of alcohol, vindictively writing that:

“Men who will fill their tanks full of whiskey, who will reel and stagger and look foolish at such times are no good anywhere. There is no excuse for filling up on such occasions. Whiskey does not good. Any man can endure physical exertion and mental strain better sober than he can with a tank full of rot-gut.”

Other writers were less harsh, but it was hard to get around the embarrassment of the drunken fire fighters.

Chief Bellis was reportedly “overcome by smoke and exhaustion” during the fire, leading to Mayor Parcher being “pressed into service as the head of the department … until the fire burned out.” Men dispatched from the fire departments of Merrill and Wisconsin Rapids arrived far too late and by then the fire had run its course.

^The burned-out remains of the Wood Opera House, 1892

The Aftermath

In the end, the fire had destroyed the entire Opera House block as well as spreading to a few nearby buildings as well. Only a few buildings had fire insurance. The Wood Opera House, the pride of Wausau, had defied all proud expectations and was lost to fire.

No one came out of the ordeal looking good.

There were many failures that contributed to that 1892 fire, but probably the biggest was the state of the firefighters. Although there was a formal company of men, they were all volunteers and so relied entirely on their day jobs to make a living. It was not as if the firefighters didn’t care about doing a good job, but rather the level of organization and competence expected was beyond what millworkers or store clerks could provide in their spare time.

If Wausau was to have an effective firefighting department, it was clear they would need to treat firefighters more like civil servants and less like volunteers.

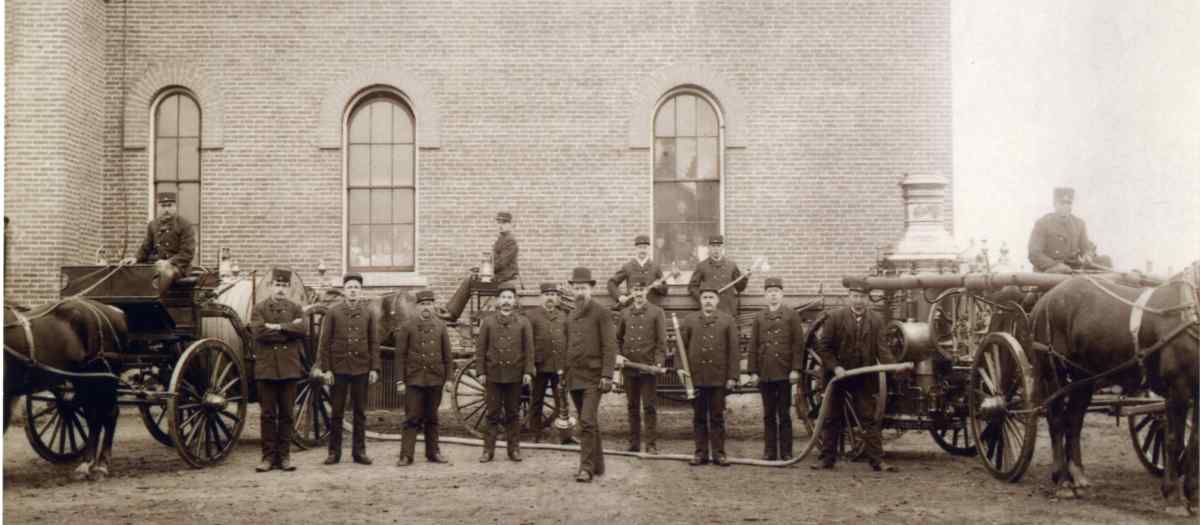

By the end of 1892, Wausau hired 12 firefighters to serve as the core of the city’s restructured Fire Department. Five years later, the Department was formally organized as part of the city government services, and required all firemen (paid and volunteers) to pass written and oral civil service examinations to prove their competence.

^Public Demonstration of the Fire Department at Humbolt School, 1890s

Further improvements were made to the infrastructure over the next few years. The water works were repaired, new fire houses were built and staffed to ensure firefighters could be dispatched quickly, and new fire alarm systems were installed at businesses and factories to detect fires at all hours of the day and night.

As for the Opera House, a new building was built where the Wood Opera House once stood. But this "Alexander Hall" was no substitute for the old Opera House, and funds were raised to build a new one. In 1899 the Grand Opera House was built a block north. While not as elegantly finished as its predecessor, it did have the advantage of a small projector to show early films. It remained until it was replaced by the Grand Theatre in 1927.